The Silk Road, as the most renowned trade and cultural exchange network across ancient Eurasia, not only shaped the patterns of global history but also sparked an enduring debate about its eastern starting point: is it Xi’an (ancient Chang’an) or Luoyang? This question is not merely a matter of geographical positioning but is embedded in the complex matrix of Chinese dynastic changes, political and economic shifts, and international heritage discourses. When the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen first coined the term “Silk Road” in 1877, he described it as a land route extending from eastern China to Europe, without specifying a single starting point. Modern academia, through archaeological evidence, historical documents, and the UNESCO framework, has gradually formed a consensus: Xi’an represents the pioneering era of the Western Han Dynasty, while Luoyang symbolizes the continuation during the Eastern Han Dynasty, together forming a dynamic starting point. This dual-starting-point model not only reflects the capital migrations of the Han and Tang empires but also embodies the essence of the Silk Road as “cultural routes”—a non-linear, adaptive network spanning time and space, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies. This article integrates historical narratives, archaeological findings, international organization documents, Western perspectives, viewpoints from various countries’ textbooks, and the latest developments from 2024-2026, to deeply analyze this debate and reveal its multifaceted foundations. Through rigorous historical verification and contemporary research, we can see that this discussion not only concerns historical facts but also involves cultural heritage preservation, geopolitics, and the interplay with the modern “Belt and Road” initiative.

The Origins of the Silk Road: Xi’an’s Pioneering Role in the Western Han and Its Geographical Foundations

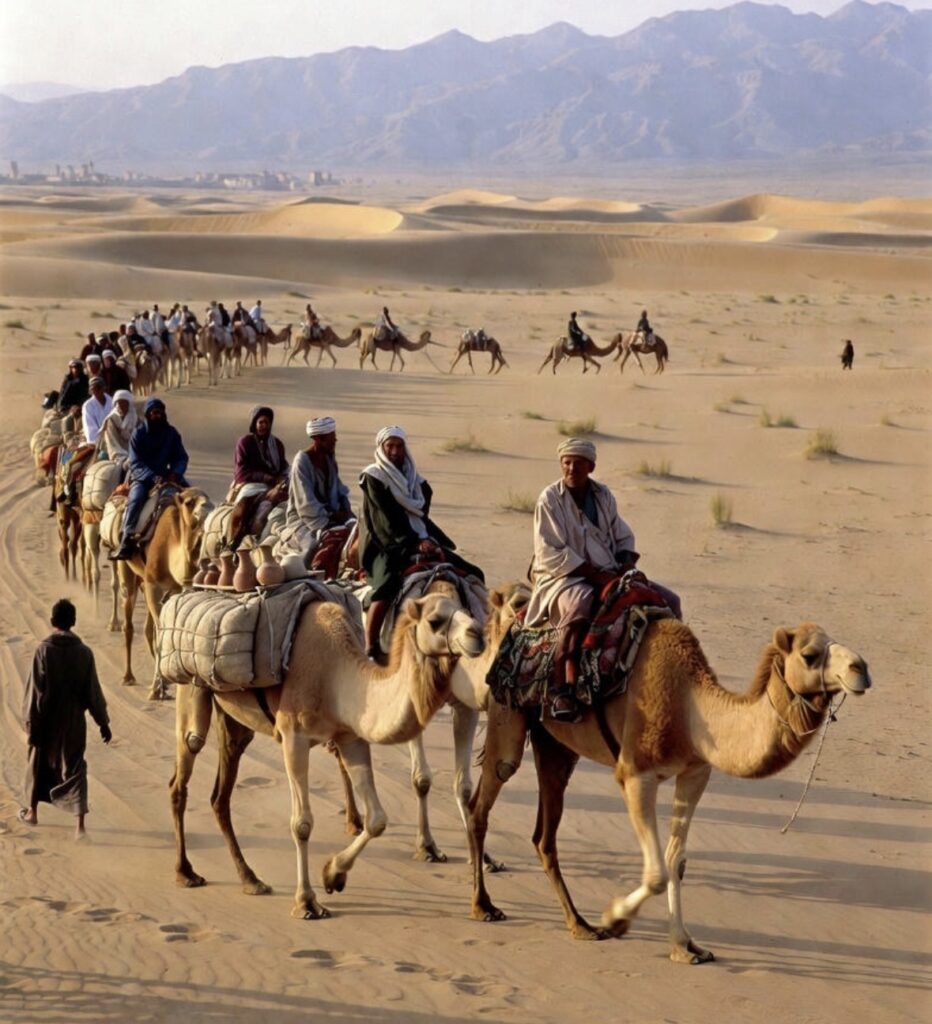

The formation of the Silk Road can be traced back to the 2nd century BCE during the Western Han Dynasty. Zhang Qian embarked on two missions to the Western Regions in 138 BCE and 115 BCE, starting from Chang’an (Xi’an), opening up the pathway to Central Asia. This marked the official inception of the Silk Road, primarily for exporting Chinese goods like silk, porcelain, and tea, while importing spices, gems, and religious ideas. According to the “Records of the Grand Historian: Treatise on the Dayuan,” Zhang Qian’s expeditions were based in Chang’an, which, as the capital of the Western Han (206 BCE to 8 CE), became the logical starting point of the route. The path extended westward from Chang’an, through the Hexi Corridor, skirting the Taklamakan Desert, and reaching the Fergana Valley. This northern route was not only a trade corridor but also involved military expansion, such as Emperor Wu of Han establishing the four commanderies in Hexi to secure the passage.

Archaeological evidence further solidifies Xi’an’s pioneering status. In Han Dynasty tombs near Xi’an, Roman glassware, Persian silver coins, and Sogdian artifacts have been unearthed, confirming the vibrancy of early trade. For instance, the Han Chang’an City site in Shaanxi Province reveals the layout of the Western Market within the city, dedicated to foreign merchants and attracting Central Asian nomads. Recent excavations, such as silk fragments and exotic gems from the Xi’an Han City site, indicate that Chang’an was not only a political center but also an economic hub. Additionally, early tea evidence—such as tea residues in Han emperor tombs (around 2100 BCE)—suggests that a branch of the Silk Road may have extended from Xi’an to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, promoting plant dissemination. These discoveries support the narrative of Xi’an as the “cradle of the Silk Road,” particularly in modern tourism, such as exhibitions at the Shaanxi Museum.

However, this pioneering era was not isolated. Scholars note that ancient capital migrations exhibited westward-to-eastward and southward-to-northward patterns, with Chang’an’s rise driven by geographical factors like the agricultural advantages of the Wei River Plain and the strategic position of the Guanzhong region, facilitating control over northwestern passages. Academic articles emphasize that Chang’an’s urban planning—including palace districts and market zones—facilitated the formation of trade networks, echoing indirect connections with the Roman Empire (as mentioned in Pliny’s “Natural History” regarding “Serica” silk). Recent studies from 2024-2025 show Xi’an revitalizing its starting-point role through the “Belt and Road” framework, such as the 2024 “Thousand-Mile Silk Road 2024: Path to Prosperity” multinational media event, emphasizing Xi’an’s continuity as an ancient and modern Silk Road hub. Furthermore, in 2025, Xi Jinping highlighted Xi’an as a cultural link to the Silk Road during a Central Asia visit, further strengthening its international image.

The Continuation and Expansion in Eastern Han Luoyang: Starting Point Shift Under Dynastic Changes and Cultural Integration

In 25 CE, the Eastern Han Dynasty was established, and the capital moved from Chang’an to Luoyang, reshaping the eastern endpoint of the Silk Road. Ban Chao conducted multiple missions to the Western Regions from 73 to 102 CE, starting from Luoyang, restoring the routes interrupted by the Xiongnu, making Luoyang the starting point of the Eastern Han Silk Road. The Southern Market in Luoyang City mirrored Chang’an’s Western Market, becoming a gathering place for Chinese and foreign merchants. The introduction of Buddhism also largely passed through Luoyang, such as An Shigao translating scriptures there in the 2nd century CE, promoting cultural exchanges. During this period, the Silk Road expanded to more branches, including southern routes connecting the Yangtze River basin via Luoyang.

Archaeological evidence is abundant: Western Regions glassware, gold and silver coins, and camel bells have been unearthed from Eastern Han Luoyang City sites, proving its status as a trade hub. Carvings of camel caravans in the Longmen Grottoes and relics from the White Horse Temple illustrate the influence of Buddhism along the route. During the Wei, Jin, and Northern Wei periods (220-534 CE), Luoyang continued as a starting point, with Emperor Xiaowen strengthening its role through capital relocation. The route adjusted to pass from Luoyang through Chang’an, then westward to Gansu and Xinjiang. Recent archaeology, such as the 2025 excavations at the Han-Wei Ancient City in Luoyang, revealed more Sogdian tombs, confirming Luoyang’s position as a multi-ethnic integration center.

Academic research, such as “Comparative Urban Zoning of Han-Wei Luoyang City and Ancient Rome,” analyzes Luoyang’s urban layout, with its grid streets and market districts adapting to Silk Road trade needs, complementing Chang’an. Some scholars criticize single-Xi’an narratives for overlooking Luoyang’s “eastern starting point” role, especially in the 7th-10th century Sui-Tang period, where Luoyang’s camel seal artifacts confirm its status. Additionally, the Xiaohan Ancient Road (from Luoyang to Tongguan) as a Silk Road branch features archaeological finds like carriage ruts and pass sites, highlighting Luoyang’s connective function. 2025 studies emphasize that Luoyang, as the capital of multiple dynasties for over 500 years after the Eastern Han, maintained the Silk Road’s eastern anchor.

The UNESCO Framework: Consensus on the Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor Dual Starting Point and Heritage Protection Dynamics

At the 2006 UNESCO conference in Xinjiang, Xi’an and Luoyang were simultaneously recognized as the eastern starting points of the Silk Road, ending local disputes. In 2014, the “Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor” was inscribed on the World Heritage List, covering a 5,000-kilometer route with 33 sites, including the Han Chang’an City and Eastern Han-Wei Luoyang City. This corridor spans China, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, active from the 2nd century BCE to the 16th century CE, emphasizing the network’s dynamism. UNESCO documents state that Chang’an represents the Han-Tang pioneering phase, while Luoyang signifies the Eastern Han continuation, avoiding a single-city thesis. The heritage includes Xi’an’s Hangu Pass and Luoyang’s Dingding Gate, embodying the pass system’s role in trade protection.

This framework has influenced global heritage protection, such as adaptive evolution studies of 22 cultural sites in western China, revealing patterns driven by climate and trade. Critics note the title’s bias toward “Chang’an,” but actual maps include Luoyang, balancing the narrative. From 2024-2026, UNESCO has seen no major updates, but related initiatives like “Belt and Road” cultural heritage cooperation have promoted new site excavations, such as Xi’an’s Silk Road relic digitization projects. This reflects a shift in heritage protection from static to dynamic, emphasizing sustainable development and transnational collaboration.

Western Perspectives: From Romanticizing Xi’an to Balancing Dual Starting Points and Contemporary Geopolitical Influences

Western historical narratives tend toward Xi’an, as in Peter Frankopan’s “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World,” which emphasizes Chang’an’s global impact. Valerie Hansen’s “The Silk Roads: A New History” acknowledges Luoyang’s revival during the Northern Wei but views Xi’an as the primary starting point. UNESCO’s consensus has prompted Western media like the BBC to cite dual starting points, avoiding Orientalist biases. However, some maps omit Luoyang due to a preference for the Western Han. 2025 Western studies, such as Jamestown Foundation reports, analyze China’s use of Silk Road starting points (like Xi’an) to advance the “Belt and Road,” viewing it as a geopolitical tool.

Diversity in Textbooks Across Countries: The Tension Between Simplification and Detail, and Educational Evolution

Chinese textbooks balance dual starting points, emphasizing dynastic changes. American materials, like McGraw-Hill’s “World History,” simplify to Xi’an. European ones (e.g., UK A-Level) are influenced by UNESCO, mentioning Luoyang’s cultural role. Japanese and Indian textbooks lean toward Xi’an, but advanced courses include Luoyang. Middle Eastern perspectives emphasize local extensions, with starting points mostly as Xi’an. Global trends, driven by UNESCO, tilt toward dual starting points. 2025 educational updates, such as India’s NCERT revisions, incorporate “Belt and Road” content, reinforcing Xi’an’s modern relevance.

Modern Significance: From Heritage to the Strategic Continuation and Cultural Revival of the “Belt and Road”

Today, the Silk Road heritage inspires the “Belt and Road” initiative, with Xi’an hosting Central Asia summits and Luoyang showcasing integration through the Longmen Grottoes. In 2025, Xi’an positioned itself as a Silk Road starting hub by hosting Routes Asia 2026. Luoyang emphasizes its role in Buddhism dissemination, such as through 2025 international exchange events. Academic works like “The History of Ancient Silk Road Development” explore its strategic importance, calling for transcending local competition. Archaeology continues, such as Qijia Culture’s metallurgical evidence tracing Silk Road origins even earlier. Social media discussions, like posts on X, highlight Xi’an’s Islamic heritage (e.g., the Great Mosque of Xi’an), linking ancient and modern Silk Roads. Future research directions include digital reconstruction and the impact of climate change on routes, enhancing heritage resilience.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Narrative of Shared Heritage and Future Prospects

The debate on the Silk Road’s starting point reveals the fluidity of history: Xi’an’s pioneering and Luoyang’s continuation are not oppositional but complementary. Through archaeology, UNESCO, and international perspectives, this dual-starting-point model has become a consensus, reminding us that the Silk Road is a shared human bridge, not a fixed path. In the era of globalization, this heritage continues to inspire cross-cultural dialogue, especially under the “Belt and Road” framework, where Xi’an and Luoyang serve as modern starting points to drive economic and cultural revival. Rigorous research emphasizes that the future requires integrating multidisciplinary methods, such as remote sensing and AI analysis, to deepen understanding of this network and avoid parochial biases.